It was a very interesting story, not least because like most of us I’m fascinated by mysteries. Whodunnits are among my favourite reads, and I’m also interested to discover local legends and traditions like the story of Mitchell’s Fold. It’s fascinating to see how people make sense of mystery, work out what’s going on, crack the code. I’ve just started reading a book about Bletchley Park, where the German Enigma Code was cracked in World War Two: remarkable people unravelling a mystery.

Which brings me to today, Trinity Sunday, a day that marks the Church’s engagement with the greatest mystery of all, the nature of God. Preachers on Trinity Sunday sometimes feel the need to delve so deeply into the various theological texts and theories that their congregations are sent to sleep within the first few minutes. All the stuff we learn at theological college but never use at any other time. Let’s see what we can do to explain the mystery of the Trinity, and unravel the mathematical formula that say “three in one and one in three”.

Or maybe we shouldn’t do any of that. Maybe we should just accept and live with the mystery and wonder of the unknowable God. Most of us live with a lot of things we don’t understand and can’t explain, even though we tend to want mysteries to be demystified. I don’t have the faintest idea how my TV or my laptops or my washing machine actually works. I don’t even understand how my toilet flushes, not really. But somehow I manage to live with those mysteries.

Of course, the reason I can live with that is that I know someone somewhere does know how these things work, and if I need to I can ring someone up who’ll come and fix them when things go wrong. Or if I do want to do it myself, I can probably find and download some instructions.

But God is unknowable, and even the best books of theology are only a set of someone’s ideas and theories. The nearest we get to understanding is the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Something we can say about God that we can all agree on, and adhere to. And it begins by admitting that God is unknowable. What Trinity goes on to do is to talk about the ways God reveals himself to us.

So the real question for today isn’t, “How can I explain God?” but “How does God seek to connect with me, and with you? And into the day-to-day living of our lives?” That’s what this doctrine is really about. What it certainly isn’t is the last word about God, the explanation at the end of the whodunnit. Trinity isn’t God summed up and explained, and neatly wrapped in a box. Trinity is us talking about how God engages with us, meets with us, and seeks a part in who we are and what we do.

Last Sunday - Pentecost or Whit Sunday - we celebrated the birth day of the Church in the fire of the Holy Spirit. The Church began, not with an explanation of things, but with a gift. God’s glory and love understood by those first apostles not as an idea or a doctrine but like fire that pulsed through their every vein. This morning’s Gospel reading has more to say about the Spirit. We hear Jesus tell his friends that “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth.”

As human beings we’re programmed to look for answers, and to make rational sense of what we see and hear and touch around us. And we may well choose to stop there and not go beyond the things we can fully understand and explain. But the Holy Spirit is given to lead us into a deeper truth than that.

A truth that isn’t about explanation but engagement. As the apostle John wrote, “No-one has ever seen God.” But God reveals himself to us: as Father, Creator, as the man Jesus Christ, who called himself Son of Man but whose disciples came to see him as Son of God, and as the Holy Spirit, God opening eyes and minds and hearts in a new way, giving us gifts, and linking us in fellowship. I think of this as God saying yes to us in three ways: the yes of creation, of our being - existing, thinking, feeling, loving; the yes of salvation, God lifting from us the burden of our failure and sin; and the yes of empowerment, God choosing and calling and equipping us to live fruitfully as his people.

I’ve been humbled by the faith I’ve found in very poor places. Maybe the complexity of our lives and our material wealth gets in the way of knowing our dependence on God. We can meet all our own needs, leaving God there to plug the occasional gap, or as an emergency support, or (sadly) as a life option we can discard. Whereas in the favelas and shanty towns and African villages I’ve visited people seem to have a deeper and more direct sense of God’s presence and call, and of the centrality of faith.

God wants to say yes to us wherever we are; he says yes most vividly in Jesus. In Christ all the love of God is there in a in human form, in a human life: in the humility of his birth; in his engagement with those whose lives needed changing, healing, transforming; and in the sacrifice of the cross.

At Easter the empty tomb changed forever the life journeys of the apostles. From the despair of Good Friday they began to see that on the cross love had won the greatest triumph: death itself had been overcome. And the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost turned a band of folk who should have been crippled by fear and failure into the fearless first missionaries of the Church: they knew God was with them; his love, like wind and fire, had made them unafraid of anything, unafraid even of death.

So the doctrine of Trinity isn’t an academic exercise designed to explain the nature of God so much as people needing to understand and use and pass on their own living experience of God, people who’d been on the road with Jesus, who’d stood by the cross, and who at Pentecost were convinced that Jesus would always be with them and they with him. And that in Jesus and in the gift of his Spirit, the power and glory of the Father was also present.

Love is the key to it all. The love that filled them as the Holy Spirit came upon them is inseparable from the love of the Father who loves us into being, and the love of the Son who saves us from sin and death. The Holy Spirit is the love of Jesus gifted among his people, and Jesus says, “I am one with the Father.”

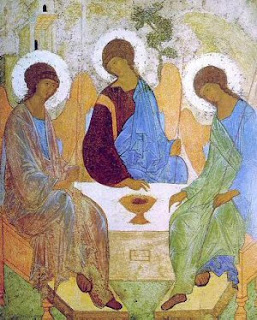

Trinity is about being drawn into the heart of God’s eternal love: Trinity tells us that relationship and love are fundamental to God. The icon on the middle pages of our weekly sheet is a very famous icon of the Trinity created by the Russian painter Andrei Rublev in the 15th century: in it, Trinity is expressed as a close and intimate relationship, a community of three, that is nonetheless also hospitable and welcoming to all. Trinity is our human attempt to speak of the God who promises always to love us, and to be with us at every turn and through every struggle.

A Church bearing the name of the Holy Trinity should therefore be a place of community and hospitality. Like the God who offers himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, and whose love is steadfast and sure, however fickle we may be.

So for me Trinity isn’t about explaining the mystery. Trinity’s about how God meets us, relates to us, leads us and calls us. He calls us to be Trinitarian: to offer hospitality, to build community, to dare to care, and to take the risk of loving. And all of this we do in praise to the God who gives himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, with a love beyond all we can imagine, and with a yes that creates and heals and equips.

No comments:

Post a Comment