(Proper 8 Year C)

“No one who puts a hand to the plough and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.”

In the days when farmers worked their land using a horse or an ox to pull the plough, they needed to be vigilant, looking ahead. Not that they don’t still - but back then, to plough a straight furrow would take the farmer's full concentration. You might look back briefly, to check that all was right behind, but if you did anything more than that, if you relaxed your concentration on the row ahead, things could go very wrong.

Jesus uses the image of the plough when responding to people who are offering themselves as disciples - and what he says to them and therefore to us is simple and stark: if you want to come with me then it’s got to be the most important thing in your life. There’s a saying that goes: “He who gives God second place gives him no place.” Discipleship is a tough ask. Some people give away all they have, throw off the trappings of the secular life, and go off to join a monastery or convent. I’ve known a few who’ve done that, and greatly admired them. But I couldn’t do the same, I know. For most of us, following Jesus is something we have to fit in to the reality of life in the secular world, earning a living, looking after families, all the stuff we have to do.

But even here, Jesus says, “Put me first; plough without looking back.” Today's Gospel begins with Jesus having “set his face to go to Jerusalem.” We know that he knows what awaits him there. He is going to Jerusalem to fulfil the task his Father has set. This is where he’ll complete the story of his obedience to his Father’s will. So today we see Jesus himself setting his hand to the plough, and not looking back, even though the road he takes, the furrow he ploughs will lead to his death. It’s a passage to stir our hearts. Jesus could have chosen to go anywhere, by any one of a thousand different ways, he had the same freedom any of us do in life. He didn’t have to go to Calvary and the cross. But he chose to do so, setting his course to Jerusalem.

“Those who set their hand on the plough and look back are not fit for the Kingdom.” Our Gospel reading will go on to mention some of those people, and we’ll see from that how to follow Jesus is never an easy ask, nor can it be part time. Several people came and offered themselves as disciples, but for each one there was a caveat, something they had to do first, something that takes priority. But before we come to those people, we might think about the Samaritan village that turned him away.

It shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that a Samaritan village should reject a Jewish teacher. Jesus was going to Jerusalem, and Samaritans didn’t accept that Jerusalem was the holy city, the right place to worship God. And anyway, Jews and Samaritans didn’t ever really mix. It shouldn’t be too much of a surprise, either, that the answer to this from the disciples of Jesus was to suggest he should call down fire from heaven to consume them. How dare these people not welcome the Master? Their minds were full of thoughts of revenge.

Jesus turned and rebuked them; for that could never be his way. We’re not told what Jesus actually said; but one ancient copy of this Gospel does include some extra words, in which Jesus points out that the Son of Man hasn’t come to destroy human lives but to save them. The Samaritans had acted out of ignorance; they’d failed to recognise who and what Jesus was.

Lots of people around us today also don’t know who Jesus is. So how do we react to them, and how should we? Not, surely, with condemnation or rejection, nor by simply ignoring them or writing them off. To be true to the example of Jesus, we should respond with patience and care, with blessing even. All that we do as Church should I think have in mind our need to reach out to and share with those who are not yet signed up to what we believe, and don’t yet know Jesus. The Alpha course we’re planning in our deanery this autumn is a case in point. And I hope that people who don’t yet know Jesus may come to recognise him there.

Anyway, then we come to Jesus among his own people. They were much more welcoming than the Samaritans had been, and indeed a number of them were keen to offer their services. “I'll follow you,” they say, “wherever you go.” The first person to say that wasn’t immediately welcomed by Jesus, however. Maybe Jesus could sense the shallowness of an offer that was skin deep rather than heart deep. It’s easy to say the words, but much harder to put those words into action. “Do you really mean what you say?” asks Jesus, in effect. “Will you really give up the comfort of your home to follow someone who has no place to lay his head?”

So with the next two encounters. There was the man who said, “I’ll come, but I must first bury my father!” And there was the man who said, “Let me first say goodbye to the people I love!” These seem to me to be quite reasonable requests, but Jesus was quite uncompromising in rejecting them. I have to admit that’s always caused me some unease. “Let the dead bury their dead!” sounds a quite uncaring thing to say. But I think the point here is that there can be no negotiating prior to saying “Yes”.

The Christian life can’t be shared by all the other loyalties and interests we have; it has to take priority. Once we set our hand to the plough, we have not to look back.

I’m reminded of the vows said at a wedding service. They are in fact acts of enslavement. Each partner gives himself, herself, completely to the other, holding nothing back, offering the whole self. Of course, we then offer back, and receive back, the freedoms we might need to make it all work: to do our own thing at times, to keep our own interests. But the complete offering of self each to other has to come first. I’m reminded also of when I first went to see my Vicar about my feeling that God might be calling me to be a priest. He did his level best to put me off - not because he didn’t think I was called, but because he wanted to make sure I’d really thought through how tough it might be.

Probably a lot of the people who flocked round Jesus and thought they might follow him were looking for a gentler ride and an easier Master. Maybe they turned away sorrowfully, wishing they could have gone with him. But it’s hard to give up the comforts and certainties of life. It’s important that anyone making a big decision is challenged. Have you really thought this through? Have you really measured what this will cost?

It’s costly and tough, but, as Paul wrote to the Galatians in our first reading, it’s the way to freedom, the freedom of the Spirit. It rather sounds as though the Galatian church wasn’t doing so well. People were falling out, and people were getting into bad ways. Paul tells them to watch out. We’re set free by the Spirit, but freedom doesn’t mean we can just do what we want and behave how we like, he tells his readers.

Paul lists the vices to be avoided. We can imagine most of those vices were part of the scene in Galatia, since Paul generally writes in response to very real situations that need sorting out. I have to say that no church today is completely immune from the same problems and issues. And occasionally things go very wrong. Human beings are fallible and frail, we make mistakes, we fall out, and sometimes we’re not nice to know, even in churches. One thing to remember, though, is that even when we’re not very loveable, and even when we don’t manage to love one another, we are all still loved by God; that simple statement has to be at the heart of all that we say and do and believe as his Church.

And Paul goes on to list the marks of a Church that is truly open to the gifting of God’s Holy Spirit. These are the things we should aim for, and this is how God’s will can be achieved and fulfilled in us - the fruits of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. This is where truly hearing the call to follow Christ should lead us. This is what should happen when we place our hand on the plough and don’t look back.

Saturday, 29 June 2019

Tuesday, 18 June 2019

Legion (a sermon)

I was reminded the other day of the story of a man whose wife rang him while he was driving along the M1 to warn him that she’d just heard reports of a car driving the wrong way down the carriageway. “One car?” he replied. “They’re wrong there - there’s hundreds of them!” What reminded me was the interesting experience I had last Saturday of coming round a roundabout - the one at the bottom of the road from Forden - heading for the Welshpool bypass, only to meet a little blue car driven by a neat elderly looking gentleman, coming straight towards me the wrong way round the roundabout. I was a bit surprised; I have to say that he seemed remarkably unconcerned.

A single wrong decision when driving can have immense and long lasting consequences. If you do happen foolishly to drive down the wrong slip road and end up on the wrong carriageway of a motorway, how do you get off? I was once driving in Basingstoke when I suddenly realised there was another carriageway to my left. My blood froze and I was on the verge of panic, until I realised that they were in the process of converting the road from single to dual carriageway, and the new carriageway was still under construction.

And what’s true of driving is equally true of much else in life. Harmful behaviour patterns can be very hard to break or change, varieties of addiction more so. It isn’t just whether you can make the changes in yourself, it’s also the way you get labelled by others, what they see in you and expect from you. If you’re travelling the wrong way down the carriageway of life, it can be very hard to find a way off. What we today might identify as mental illness, addictive behaviour, or perhaps criminal or sociopathic tendencies, would in past times have been thought of in terms of demon possession. And the man in today’s story had gone a very long way down the wrong carriageway; he’d acquired loads of demons. People had given up on him and were afraid of him, so there he was, living in squalor among the tombs.

It’s an amazing and very dramatic story, but we may be tempted to disregard it because we don’t think in terms of demon possession these days, or most of us don’t; and maybe even because we feel bad about Jesus allowing all those pigs to jump to their deaths.

But I think it’s a story with much to tell us and to teach us. And though we might reject the idea of people being possessed by demons, people living with certain forms of mental illness would relate to it very well. That’s what it can feel like to them: that other voices are controlling and seeking to direct them. And to be honest all of us probably know times when we say in exasperation, “I no longer feel in control of my own life!”

Nowadays we can identify a genetic component to schizophrenia, and we can see how forms of paranoia are linked to the abuse of certain drugs, like skunk marijuana, or related to post traumatic stress disorder. Our understanding of mental illness has grown, but it still inspires fear. Bad decisions and bad things that happen can set a person down a wrong carriageway they can’t get off, not on their own, anyway. But along the way, they may scare other people, who shun them and write them off.

The man in today’s story had been so written off, and people were so afraid of him, that he’d become as good as dead, or maybe he just wished he was dead. He lived among the tombs. I guess there were people in the village who still cared about him, but they were afraid and they didn’t know what to do. The best they could think of was to chain him up, but that didn’t work. We may talk about a “complex” when referring to types of mental illness; it isn’t easy to unravel things once you’ve travelled a long way down the wrong road. In our reading that translates as being possessed by so many demons that he gave the name “Legion”. But some part of him wanted release, which is why he met Jesus, while much within him didn’t, was too far gone, which is why he spoke as he did. But Jesus had time and patience and compassion for a man everyone else had written off.

The story itself gets quite strange: the demons negotiate with Jesus, effectively, and Jesus allows them to go into the pigs rather than being banished altogether, upon which the entire herd of pigs rushes over a cliff and is drowned in the lake - which was bad news for the pigs, and also for their swineherd! Pigs of course are unclean animals for Jews, so maybe they didn’t matter too much. William Barclay, in his commentary on this passage, suggests that the destruction of the pigs was necessary to demonstrate to the man that his demons really had gone for good. But for me it speaks simply and starkly about the destructive power of the things - the habits, the abuses - that we allow wrongly to take control in our lives. They can be deadly.

Bad decisions, bad advisers build on themselves, so that they take us further and further along the wrong road. Depression or not being able to sort things out, face up to problems, conquer fears, or live with a sense of failure or loneliness may lead a person to take solace in alcohol or some other drug, which may seem to make things better but in the end only make them worse.

May I say, by the way, that I’m not only talking about what we diagnose as mental illness. I don’t in fact believe there is a clear boundary between sanity and mental illness. The things that are out of control in a person we label as mentally ill are to a degree shared by all of us. And any one of us is capable of making bad choices in life, putting our trust in the wrong petty gods or the wrong human prophets.

The people of the town reacted to the healing of the man there by the lake by telling Jesus to go away. Barclay talks about them not wanting the balance of their lives disturbed. He may be right there, since they do seem to have quickly realised that a person with this much power would be an uncomfortable presence. He’d want to change them too. To accept Jesus we do need to accept the need for change: “You can’t follow me and look back,” he said to his disciples. And that could translate into, for example:

You can’t follow me and still make people work for you under such bad conditions; you can’t follow me and still have racist opinions; you can’t follow me and still be wasteful in the way you use the earth’s resources; you can’t follow me and still be prepared to allow people to live in substandard housing. He might well be saying all of this to us and more. He might even be saying, you can’t follow me and still walk past or abandon or lock up those who are mentally ill. And anyway, it isn’t only the obviously and scarily mentally ill who are in the grip of bad decisions.

Here’s where my initial story of the man going the wrong way down the motorway breaks down a bit. Going with Jesus may often be the exact opposite of going along with the crowd. Maybe the man seeing all those drivers coming towards him was after all the only one going in the right direction. The man cured of those demons wanted to stay with Jesus, but Jesus sent him home instead - to those very people who’d told him to go away and leave them alone. It’s easy to be a Christian when I’m away on retreat in some holy place; but the place where Jesus needs me to be a Christian (and you too) is here in the place where I am, and now in the hour that I’ve got, and of course not only on a Sunday, but tomorrow too.

A single wrong decision when driving can have immense and long lasting consequences. If you do happen foolishly to drive down the wrong slip road and end up on the wrong carriageway of a motorway, how do you get off? I was once driving in Basingstoke when I suddenly realised there was another carriageway to my left. My blood froze and I was on the verge of panic, until I realised that they were in the process of converting the road from single to dual carriageway, and the new carriageway was still under construction.

And what’s true of driving is equally true of much else in life. Harmful behaviour patterns can be very hard to break or change, varieties of addiction more so. It isn’t just whether you can make the changes in yourself, it’s also the way you get labelled by others, what they see in you and expect from you. If you’re travelling the wrong way down the carriageway of life, it can be very hard to find a way off. What we today might identify as mental illness, addictive behaviour, or perhaps criminal or sociopathic tendencies, would in past times have been thought of in terms of demon possession. And the man in today’s story had gone a very long way down the wrong carriageway; he’d acquired loads of demons. People had given up on him and were afraid of him, so there he was, living in squalor among the tombs.

It’s an amazing and very dramatic story, but we may be tempted to disregard it because we don’t think in terms of demon possession these days, or most of us don’t; and maybe even because we feel bad about Jesus allowing all those pigs to jump to their deaths.

But I think it’s a story with much to tell us and to teach us. And though we might reject the idea of people being possessed by demons, people living with certain forms of mental illness would relate to it very well. That’s what it can feel like to them: that other voices are controlling and seeking to direct them. And to be honest all of us probably know times when we say in exasperation, “I no longer feel in control of my own life!”

Nowadays we can identify a genetic component to schizophrenia, and we can see how forms of paranoia are linked to the abuse of certain drugs, like skunk marijuana, or related to post traumatic stress disorder. Our understanding of mental illness has grown, but it still inspires fear. Bad decisions and bad things that happen can set a person down a wrong carriageway they can’t get off, not on their own, anyway. But along the way, they may scare other people, who shun them and write them off.

The man in today’s story had been so written off, and people were so afraid of him, that he’d become as good as dead, or maybe he just wished he was dead. He lived among the tombs. I guess there were people in the village who still cared about him, but they were afraid and they didn’t know what to do. The best they could think of was to chain him up, but that didn’t work. We may talk about a “complex” when referring to types of mental illness; it isn’t easy to unravel things once you’ve travelled a long way down the wrong road. In our reading that translates as being possessed by so many demons that he gave the name “Legion”. But some part of him wanted release, which is why he met Jesus, while much within him didn’t, was too far gone, which is why he spoke as he did. But Jesus had time and patience and compassion for a man everyone else had written off.

The story itself gets quite strange: the demons negotiate with Jesus, effectively, and Jesus allows them to go into the pigs rather than being banished altogether, upon which the entire herd of pigs rushes over a cliff and is drowned in the lake - which was bad news for the pigs, and also for their swineherd! Pigs of course are unclean animals for Jews, so maybe they didn’t matter too much. William Barclay, in his commentary on this passage, suggests that the destruction of the pigs was necessary to demonstrate to the man that his demons really had gone for good. But for me it speaks simply and starkly about the destructive power of the things - the habits, the abuses - that we allow wrongly to take control in our lives. They can be deadly.

Bad decisions, bad advisers build on themselves, so that they take us further and further along the wrong road. Depression or not being able to sort things out, face up to problems, conquer fears, or live with a sense of failure or loneliness may lead a person to take solace in alcohol or some other drug, which may seem to make things better but in the end only make them worse.

May I say, by the way, that I’m not only talking about what we diagnose as mental illness. I don’t in fact believe there is a clear boundary between sanity and mental illness. The things that are out of control in a person we label as mentally ill are to a degree shared by all of us. And any one of us is capable of making bad choices in life, putting our trust in the wrong petty gods or the wrong human prophets.

The people of the town reacted to the healing of the man there by the lake by telling Jesus to go away. Barclay talks about them not wanting the balance of their lives disturbed. He may be right there, since they do seem to have quickly realised that a person with this much power would be an uncomfortable presence. He’d want to change them too. To accept Jesus we do need to accept the need for change: “You can’t follow me and look back,” he said to his disciples. And that could translate into, for example:

You can’t follow me and still make people work for you under such bad conditions; you can’t follow me and still have racist opinions; you can’t follow me and still be wasteful in the way you use the earth’s resources; you can’t follow me and still be prepared to allow people to live in substandard housing. He might well be saying all of this to us and more. He might even be saying, you can’t follow me and still walk past or abandon or lock up those who are mentally ill. And anyway, it isn’t only the obviously and scarily mentally ill who are in the grip of bad decisions.

Here’s where my initial story of the man going the wrong way down the motorway breaks down a bit. Going with Jesus may often be the exact opposite of going along with the crowd. Maybe the man seeing all those drivers coming towards him was after all the only one going in the right direction. The man cured of those demons wanted to stay with Jesus, but Jesus sent him home instead - to those very people who’d told him to go away and leave them alone. It’s easy to be a Christian when I’m away on retreat in some holy place; but the place where Jesus needs me to be a Christian (and you too) is here in the place where I am, and now in the hour that I’ve got, and of course not only on a Sunday, but tomorrow too.

Saturday, 15 June 2019

A Sermon for Trinity Sunday

I saw something in my paper the other day that rather startled me. “Asteroid near miss on Scotland” read the headline. Wow, I thought, how come I never heard about that? When I read the article I discovered that the near miss actually happened some half a billion years ago. But scientists it seems are just now making sense of the evidence off the west coast of Scotland, unravelling the mystery of a traumatic event from very long ago, that they can still read in the rocks deep below the waves.

It was a very interesting story, not least because like most of us I’m fascinated by mysteries. Whodunnits are among my favourite reads, and I’m also interested to discover local legends and traditions like the story of Mitchell’s Fold. It’s fascinating to see how people make sense of mystery, work out what’s going on, crack the code. I’ve just started reading a book about Bletchley Park, where the German Enigma Code was cracked in World War Two: remarkable people unravelling a mystery.

Which brings me to today, Trinity Sunday, a day that marks the Church’s engagement with the greatest mystery of all, the nature of God. Preachers on Trinity Sunday sometimes feel the need to delve so deeply into the various theological texts and theories that their congregations are sent to sleep within the first few minutes. All the stuff we learn at theological college but never use at any other time. Let’s see what we can do to explain the mystery of the Trinity, and unravel the mathematical formula that say “three in one and one in three”.

Or maybe we shouldn’t do any of that. Maybe we should just accept and live with the mystery and wonder of the unknowable God. Most of us live with a lot of things we don’t understand and can’t explain, even though we tend to want mysteries to be demystified. I don’t have the faintest idea how my TV or my laptops or my washing machine actually works. I don’t even understand how my toilet flushes, not really. But somehow I manage to live with those mysteries.

Of course, the reason I can live with that is that I know someone somewhere does know how these things work, and if I need to I can ring someone up who’ll come and fix them when things go wrong. Or if I do want to do it myself, I can probably find and download some instructions.

But God is unknowable, and even the best books of theology are only a set of someone’s ideas and theories. The nearest we get to understanding is the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Something we can say about God that we can all agree on, and adhere to. And it begins by admitting that God is unknowable. What Trinity goes on to do is to talk about the ways God reveals himself to us.

So the real question for today isn’t, “How can I explain God?” but “How does God seek to connect with me, and with you? And into the day-to-day living of our lives?” That’s what this doctrine is really about. What it certainly isn’t is the last word about God, the explanation at the end of the whodunnit. Trinity isn’t God summed up and explained, and neatly wrapped in a box. Trinity is us talking about how God engages with us, meets with us, and seeks a part in who we are and what we do.

Last Sunday - Pentecost or Whit Sunday - we celebrated the birth day of the Church in the fire of the Holy Spirit. The Church began, not with an explanation of things, but with a gift. God’s glory and love understood by those first apostles not as an idea or a doctrine but like fire that pulsed through their every vein. This morning’s Gospel reading has more to say about the Spirit. We hear Jesus tell his friends that “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth.”

As human beings we’re programmed to look for answers, and to make rational sense of what we see and hear and touch around us. And we may well choose to stop there and not go beyond the things we can fully understand and explain. But the Holy Spirit is given to lead us into a deeper truth than that.

A truth that isn’t about explanation but engagement. As the apostle John wrote, “No-one has ever seen God.” But God reveals himself to us: as Father, Creator, as the man Jesus Christ, who called himself Son of Man but whose disciples came to see him as Son of God, and as the Holy Spirit, God opening eyes and minds and hearts in a new way, giving us gifts, and linking us in fellowship. I think of this as God saying yes to us in three ways: the yes of creation, of our being - existing, thinking, feeling, loving; the yes of salvation, God lifting from us the burden of our failure and sin; and the yes of empowerment, God choosing and calling and equipping us to live fruitfully as his people.

I’ve been humbled by the faith I’ve found in very poor places. Maybe the complexity of our lives and our material wealth gets in the way of knowing our dependence on God. We can meet all our own needs, leaving God there to plug the occasional gap, or as an emergency support, or (sadly) as a life option we can discard. Whereas in the favelas and shanty towns and African villages I’ve visited people seem to have a deeper and more direct sense of God’s presence and call, and of the centrality of faith.

God wants to say yes to us wherever we are; he says yes most vividly in Jesus. In Christ all the love of God is there in a in human form, in a human life: in the humility of his birth; in his engagement with those whose lives needed changing, healing, transforming; and in the sacrifice of the cross.

At Easter the empty tomb changed forever the life journeys of the apostles. From the despair of Good Friday they began to see that on the cross love had won the greatest triumph: death itself had been overcome. And the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost turned a band of folk who should have been crippled by fear and failure into the fearless first missionaries of the Church: they knew God was with them; his love, like wind and fire, had made them unafraid of anything, unafraid even of death.

So the doctrine of Trinity isn’t an academic exercise designed to explain the nature of God so much as people needing to understand and use and pass on their own living experience of God, people who’d been on the road with Jesus, who’d stood by the cross, and who at Pentecost were convinced that Jesus would always be with them and they with him. And that in Jesus and in the gift of his Spirit, the power and glory of the Father was also present.

Love is the key to it all. The love that filled them as the Holy Spirit came upon them is inseparable from the love of the Father who loves us into being, and the love of the Son who saves us from sin and death. The Holy Spirit is the love of Jesus gifted among his people, and Jesus says, “I am one with the Father.”

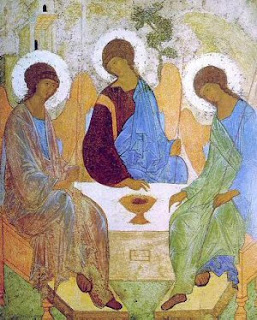

Trinity is about being drawn into the heart of God’s eternal love: Trinity tells us that relationship and love are fundamental to God. The icon on the middle pages of our weekly sheet is a very famous icon of the Trinity created by the Russian painter Andrei Rublev in the 15th century: in it, Trinity is expressed as a close and intimate relationship, a community of three, that is nonetheless also hospitable and welcoming to all. Trinity is our human attempt to speak of the God who promises always to love us, and to be with us at every turn and through every struggle.

A Church bearing the name of the Holy Trinity should therefore be a place of community and hospitality. Like the God who offers himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, and whose love is steadfast and sure, however fickle we may be.

So for me Trinity isn’t about explaining the mystery. Trinity’s about how God meets us, relates to us, leads us and calls us. He calls us to be Trinitarian: to offer hospitality, to build community, to dare to care, and to take the risk of loving. And all of this we do in praise to the God who gives himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, with a love beyond all we can imagine, and with a yes that creates and heals and equips.

It was a very interesting story, not least because like most of us I’m fascinated by mysteries. Whodunnits are among my favourite reads, and I’m also interested to discover local legends and traditions like the story of Mitchell’s Fold. It’s fascinating to see how people make sense of mystery, work out what’s going on, crack the code. I’ve just started reading a book about Bletchley Park, where the German Enigma Code was cracked in World War Two: remarkable people unravelling a mystery.

Which brings me to today, Trinity Sunday, a day that marks the Church’s engagement with the greatest mystery of all, the nature of God. Preachers on Trinity Sunday sometimes feel the need to delve so deeply into the various theological texts and theories that their congregations are sent to sleep within the first few minutes. All the stuff we learn at theological college but never use at any other time. Let’s see what we can do to explain the mystery of the Trinity, and unravel the mathematical formula that say “three in one and one in three”.

Or maybe we shouldn’t do any of that. Maybe we should just accept and live with the mystery and wonder of the unknowable God. Most of us live with a lot of things we don’t understand and can’t explain, even though we tend to want mysteries to be demystified. I don’t have the faintest idea how my TV or my laptops or my washing machine actually works. I don’t even understand how my toilet flushes, not really. But somehow I manage to live with those mysteries.

Of course, the reason I can live with that is that I know someone somewhere does know how these things work, and if I need to I can ring someone up who’ll come and fix them when things go wrong. Or if I do want to do it myself, I can probably find and download some instructions.

But God is unknowable, and even the best books of theology are only a set of someone’s ideas and theories. The nearest we get to understanding is the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Something we can say about God that we can all agree on, and adhere to. And it begins by admitting that God is unknowable. What Trinity goes on to do is to talk about the ways God reveals himself to us.

So the real question for today isn’t, “How can I explain God?” but “How does God seek to connect with me, and with you? And into the day-to-day living of our lives?” That’s what this doctrine is really about. What it certainly isn’t is the last word about God, the explanation at the end of the whodunnit. Trinity isn’t God summed up and explained, and neatly wrapped in a box. Trinity is us talking about how God engages with us, meets with us, and seeks a part in who we are and what we do.

Last Sunday - Pentecost or Whit Sunday - we celebrated the birth day of the Church in the fire of the Holy Spirit. The Church began, not with an explanation of things, but with a gift. God’s glory and love understood by those first apostles not as an idea or a doctrine but like fire that pulsed through their every vein. This morning’s Gospel reading has more to say about the Spirit. We hear Jesus tell his friends that “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth.”

As human beings we’re programmed to look for answers, and to make rational sense of what we see and hear and touch around us. And we may well choose to stop there and not go beyond the things we can fully understand and explain. But the Holy Spirit is given to lead us into a deeper truth than that.

A truth that isn’t about explanation but engagement. As the apostle John wrote, “No-one has ever seen God.” But God reveals himself to us: as Father, Creator, as the man Jesus Christ, who called himself Son of Man but whose disciples came to see him as Son of God, and as the Holy Spirit, God opening eyes and minds and hearts in a new way, giving us gifts, and linking us in fellowship. I think of this as God saying yes to us in three ways: the yes of creation, of our being - existing, thinking, feeling, loving; the yes of salvation, God lifting from us the burden of our failure and sin; and the yes of empowerment, God choosing and calling and equipping us to live fruitfully as his people.

I’ve been humbled by the faith I’ve found in very poor places. Maybe the complexity of our lives and our material wealth gets in the way of knowing our dependence on God. We can meet all our own needs, leaving God there to plug the occasional gap, or as an emergency support, or (sadly) as a life option we can discard. Whereas in the favelas and shanty towns and African villages I’ve visited people seem to have a deeper and more direct sense of God’s presence and call, and of the centrality of faith.

God wants to say yes to us wherever we are; he says yes most vividly in Jesus. In Christ all the love of God is there in a in human form, in a human life: in the humility of his birth; in his engagement with those whose lives needed changing, healing, transforming; and in the sacrifice of the cross.

At Easter the empty tomb changed forever the life journeys of the apostles. From the despair of Good Friday they began to see that on the cross love had won the greatest triumph: death itself had been overcome. And the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost turned a band of folk who should have been crippled by fear and failure into the fearless first missionaries of the Church: they knew God was with them; his love, like wind and fire, had made them unafraid of anything, unafraid even of death.

So the doctrine of Trinity isn’t an academic exercise designed to explain the nature of God so much as people needing to understand and use and pass on their own living experience of God, people who’d been on the road with Jesus, who’d stood by the cross, and who at Pentecost were convinced that Jesus would always be with them and they with him. And that in Jesus and in the gift of his Spirit, the power and glory of the Father was also present.

Love is the key to it all. The love that filled them as the Holy Spirit came upon them is inseparable from the love of the Father who loves us into being, and the love of the Son who saves us from sin and death. The Holy Spirit is the love of Jesus gifted among his people, and Jesus says, “I am one with the Father.”

Trinity is about being drawn into the heart of God’s eternal love: Trinity tells us that relationship and love are fundamental to God. The icon on the middle pages of our weekly sheet is a very famous icon of the Trinity created by the Russian painter Andrei Rublev in the 15th century: in it, Trinity is expressed as a close and intimate relationship, a community of three, that is nonetheless also hospitable and welcoming to all. Trinity is our human attempt to speak of the God who promises always to love us, and to be with us at every turn and through every struggle.

A Church bearing the name of the Holy Trinity should therefore be a place of community and hospitality. Like the God who offers himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, and whose love is steadfast and sure, however fickle we may be.

So for me Trinity isn’t about explaining the mystery. Trinity’s about how God meets us, relates to us, leads us and calls us. He calls us to be Trinitarian: to offer hospitality, to build community, to dare to care, and to take the risk of loving. And all of this we do in praise to the God who gives himself to us as Father and Son and Spirit, with a love beyond all we can imagine, and with a yes that creates and heals and equips.

Sunday, 9 June 2019

Pentecost (sermon)

“Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and still you do not know me?” That’s what Jesus says to Philip at the beginning of today’s Gospel reading, and they’re words that speak to my own doubts and uncertainties. Sometimes and in some places I’m sure and confident about what I believe, but that’s not true all the time. Sometimes faith’s a struggle, and my sense of being called gets weak and faint. And maybe Jesus is asking the same question of me: “Have I been with you all this time and still you don’t know me?”

Pentecost was one of the big Jewish festivals, not as important as the Passover, but big enough to bring a lot of people into Jerusalem. The wine harvest happened at Pentecost, which is why some people were quick to dismiss the joyful band of disciples that day as having drunk too much of the new wine.

But they’d been filled with the new wine not of the grape but of God’s Holy Spirit. And all the ifs and buts of faith, all its uncertainties and inhibitions, had been lifted from them, to leave them full of wonder and delight: each of them experiencing God’s love in a deeply personal way: as flames, distributed, and resting on each of them - that’s how it’s described. But also as something shared and bringing them into a new closeness together, as they were so powerfully made aware of the closeness of God, and the triumph of his love.

I’ve got lots of favourite hymns, one of which we’ve already sung this morning: “Come down, O love divine.” Any top ten of my favourites would probably be different on any different day. But if there’s one hymn I think would always be there, it’s the one that begins “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy like the wideness of the sea.” These days it’s often sung to a great new tune which must be of fairly local origin as it’s called “Corvedale”. But I also sing it to an old Welsh tune as a solo at concerts; and I sang it recently at the memorial service for a friend.

I like this hymn so much because its theme about how when our faith gets officious and judgemental and narrow minded we’ve lost touch with God’s generosity and grace. And these words especially always strike home: “But we make his love too narrow by false limits of our own, and we magnify his strictness with a zeal he will not own.” I’m sure God always sees further than the narrow judgements we make, and is more generous by far than our moral strictness. The Holy Spirit came upon the disciples on that first Christian Pentecost as a direct experience of transforming love. They were so overcome with joy because they knew, not just as an idea or doctrinal statement but as something that ran through them like fire, just how much they were loved. That’s why they went straight out onto the streets to tell people.

But there was a day after Pentecost, and a day after that. Even for those first fired-up Christians there’d be days when faith was more a slog than a dance, days when the skies and the streets were cold and grey. Last week at morning prayer I was reading from the first Letter of John; and in chapter 2 John writes about those in whom the fire had obviously cooled, for they’d left the fellowship and gone their own way.

Nearly forty years ago I was made a deacon, and I remember the day clearly. It felt like Pentecost: I was on a real spiritual high, with the sense of God welcoming me in with the gift of his Spirit, on that special Sunday. But I remember the Monday that followed too, when the real task of ministry began, and my sense of being fully called and equipped wasn’t quite so strong.

My ministry’s never been an easy ride. It’s included some great times, but sometimes I’ve fallen out of love with the Church, and at times it’s annoyed or appalled me. But I haven’t always got it right either. As Paul wrote, God entrusts his message of love to mere earthenware vessels, to us fallible and breakable human beings. At times we do make his love too narrow. But Jesus has promised not to leave us without help: to send his Holy Spirit.

On that first Christian day of Pentecost, narrowness was done away with, and barriers were broken down. People from all over the world could hear the apostles speaking to them in their own language. Amazing! So what really happened?

People from all over the place could hear good news preached in a way they could understand. They’d all have been Jews, or else proselytes, believers who worshipped alongside Jews. It took a bit longer for the Gospel to reach across the barrier that separated the Jewish world from the world beyond. And probably all these people spoke Greek, since Koine or common Greek was very widely spoken across the Roman Empire.

Not a real miracle after all then, you might say. But a miracle is much more than a magic trick. The miracle of Pentecost isn’t really the speaking in tongues, however that actually happened; it’s the fact that, as those tongues of fire rested on the heads of the disciples, the barriers were broken down between what’s divine and what is of the earth, between the sacred and the secular, and between every sort and class and race of people.

God’s love is for everyone, and within that love we see one another and understand one another in a new way. Each one of us is someone loved by God, someone bearing his image. Wherever we are, God is with us, longing for us to turn to him and open our hearts to him, longing to fill us with the radiance of his love: a love that is immeasurably broad and wide and deep.

And that love shone in the life of Jesus, which is why he asks, “Have I been with you all this time and still you do not know me?” And I don’t always know him. On those grey and dismal times when prayers are hard to come by, I find myself thinking that however loudly I speak them they won’t be heard. Is that because I make his love too narrow, by false limits of my own? Am I closing my eyes to things I should be seeing? Have I settled for a smaller, more manageable God, who fits into my lifestyle?

All of those things, at times. And maybe also it’s just that things are no longer as fresh and new as they once were. God is always doing new things; his love is always sparking off new and beautiful events, changing lives, healing situations. But maybe at times I’ve been looking in the wrong places. I might expect to find God in church, but he isn’t locked inside this or any other sacred building. The message of Pentecost is: “Wherever two or three are gathered together, there am I in your midst” - God’s promise to be always with us. We can build walls around the places where God’s supposed to be, and try and dictate the places in which he belongs. But it won’t work. The message of Pentecost is that God doesn’t stay where we try to put him.

Today’s Gospel reading challenges us to see God in new ways; to open our eyes wider, to open our minds and our hearts wider too. By all means look for God in churches and cathedrals, but don’t expect to only find him there; see him also at work in the kindness of strangers, in the beauty of the natural world, in each person who takes risks in the name of justice and peace, in each person who reaches out to people who are weak or needy or broken or hurting. The message of Pentecost takes us out of our own comfort zone to see further: as the Taize chant puts it “Ubi caritas, et amor, deus ibi est” (Wherever love and charity are, God is there). Barriers were broken on the birth day of the Church, and when barriers get torn down there’ll always be a sense that we’re stepping into the unknown.

That’s certainly what the disciples did that day, as they left the safety of their lodging to shout and sing and laugh and pray out on the streets. And there on the streets of Jerusalem the Church was born. And they and we are met in ministry and mission by a love beyond words, and the assurance that in God the unknown and unknowable, we are known; we are treasured; we have a place in his love; we find in him our true and lasting home.

Pentecost was one of the big Jewish festivals, not as important as the Passover, but big enough to bring a lot of people into Jerusalem. The wine harvest happened at Pentecost, which is why some people were quick to dismiss the joyful band of disciples that day as having drunk too much of the new wine.

But they’d been filled with the new wine not of the grape but of God’s Holy Spirit. And all the ifs and buts of faith, all its uncertainties and inhibitions, had been lifted from them, to leave them full of wonder and delight: each of them experiencing God’s love in a deeply personal way: as flames, distributed, and resting on each of them - that’s how it’s described. But also as something shared and bringing them into a new closeness together, as they were so powerfully made aware of the closeness of God, and the triumph of his love.

I’ve got lots of favourite hymns, one of which we’ve already sung this morning: “Come down, O love divine.” Any top ten of my favourites would probably be different on any different day. But if there’s one hymn I think would always be there, it’s the one that begins “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy like the wideness of the sea.” These days it’s often sung to a great new tune which must be of fairly local origin as it’s called “Corvedale”. But I also sing it to an old Welsh tune as a solo at concerts; and I sang it recently at the memorial service for a friend.

I like this hymn so much because its theme about how when our faith gets officious and judgemental and narrow minded we’ve lost touch with God’s generosity and grace. And these words especially always strike home: “But we make his love too narrow by false limits of our own, and we magnify his strictness with a zeal he will not own.” I’m sure God always sees further than the narrow judgements we make, and is more generous by far than our moral strictness. The Holy Spirit came upon the disciples on that first Christian Pentecost as a direct experience of transforming love. They were so overcome with joy because they knew, not just as an idea or doctrinal statement but as something that ran through them like fire, just how much they were loved. That’s why they went straight out onto the streets to tell people.

But there was a day after Pentecost, and a day after that. Even for those first fired-up Christians there’d be days when faith was more a slog than a dance, days when the skies and the streets were cold and grey. Last week at morning prayer I was reading from the first Letter of John; and in chapter 2 John writes about those in whom the fire had obviously cooled, for they’d left the fellowship and gone their own way.

Nearly forty years ago I was made a deacon, and I remember the day clearly. It felt like Pentecost: I was on a real spiritual high, with the sense of God welcoming me in with the gift of his Spirit, on that special Sunday. But I remember the Monday that followed too, when the real task of ministry began, and my sense of being fully called and equipped wasn’t quite so strong.

My ministry’s never been an easy ride. It’s included some great times, but sometimes I’ve fallen out of love with the Church, and at times it’s annoyed or appalled me. But I haven’t always got it right either. As Paul wrote, God entrusts his message of love to mere earthenware vessels, to us fallible and breakable human beings. At times we do make his love too narrow. But Jesus has promised not to leave us without help: to send his Holy Spirit.

On that first Christian day of Pentecost, narrowness was done away with, and barriers were broken down. People from all over the world could hear the apostles speaking to them in their own language. Amazing! So what really happened?

People from all over the place could hear good news preached in a way they could understand. They’d all have been Jews, or else proselytes, believers who worshipped alongside Jews. It took a bit longer for the Gospel to reach across the barrier that separated the Jewish world from the world beyond. And probably all these people spoke Greek, since Koine or common Greek was very widely spoken across the Roman Empire.

Not a real miracle after all then, you might say. But a miracle is much more than a magic trick. The miracle of Pentecost isn’t really the speaking in tongues, however that actually happened; it’s the fact that, as those tongues of fire rested on the heads of the disciples, the barriers were broken down between what’s divine and what is of the earth, between the sacred and the secular, and between every sort and class and race of people.

God’s love is for everyone, and within that love we see one another and understand one another in a new way. Each one of us is someone loved by God, someone bearing his image. Wherever we are, God is with us, longing for us to turn to him and open our hearts to him, longing to fill us with the radiance of his love: a love that is immeasurably broad and wide and deep.

And that love shone in the life of Jesus, which is why he asks, “Have I been with you all this time and still you do not know me?” And I don’t always know him. On those grey and dismal times when prayers are hard to come by, I find myself thinking that however loudly I speak them they won’t be heard. Is that because I make his love too narrow, by false limits of my own? Am I closing my eyes to things I should be seeing? Have I settled for a smaller, more manageable God, who fits into my lifestyle?

All of those things, at times. And maybe also it’s just that things are no longer as fresh and new as they once were. God is always doing new things; his love is always sparking off new and beautiful events, changing lives, healing situations. But maybe at times I’ve been looking in the wrong places. I might expect to find God in church, but he isn’t locked inside this or any other sacred building. The message of Pentecost is: “Wherever two or three are gathered together, there am I in your midst” - God’s promise to be always with us. We can build walls around the places where God’s supposed to be, and try and dictate the places in which he belongs. But it won’t work. The message of Pentecost is that God doesn’t stay where we try to put him.

Today’s Gospel reading challenges us to see God in new ways; to open our eyes wider, to open our minds and our hearts wider too. By all means look for God in churches and cathedrals, but don’t expect to only find him there; see him also at work in the kindness of strangers, in the beauty of the natural world, in each person who takes risks in the name of justice and peace, in each person who reaches out to people who are weak or needy or broken or hurting. The message of Pentecost takes us out of our own comfort zone to see further: as the Taize chant puts it “Ubi caritas, et amor, deus ibi est” (Wherever love and charity are, God is there). Barriers were broken on the birth day of the Church, and when barriers get torn down there’ll always be a sense that we’re stepping into the unknown.

That’s certainly what the disciples did that day, as they left the safety of their lodging to shout and sing and laugh and pray out on the streets. And there on the streets of Jerusalem the Church was born. And they and we are met in ministry and mission by a love beyond words, and the assurance that in God the unknown and unknowable, we are known; we are treasured; we have a place in his love; we find in him our true and lasting home.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)