Next Sunday we start a new church year, as the season of Advent begins. And of course we’ll be looking forward to Christmas, and our celebration of the birth of Jesus. So it may feel a bit odd that our Gospel reading this morning should be something from the other end of that story, part of Luke’s account of the death of Jesus.

But we end our church year by acclaiming Christ the King, and for me this Gospel reading provides an important insight into what his kingship means, and how it’s proclaimed. Our own royal family has been in the news this last week, and not necessarily for good reasons. My paper was headlined “Crisis at the Palace”. I think we all have huge respect for our Queen, and rightly so; she’s served country and commonwealth well, and with a deep sense of duty, both to her people and to God. Nothing can take that away; but respect for the family as a whole has been dented by recent events.

But if we’re looking for leaders, where else do we go? We’re in the midst of a general election campaign that it seems no-one wants, though some may agree that it’s necessary. People I’ve spoken with over the past week or two, whichever way they’ve decided to vote (assuming they’re even going to vote), most of them seem to have the philosophy of voting for the least worst option. “Not one of the lot of them is any good!” I was told yesterday.

It’s no surprise that many people over the past few months have come to see the political establishment as both inept and self-serving. Leading candidates on every side see no need to correct or apologise for false and inaccurate claims or counter claims, and instead simply repeat them. On Christ the King Sunday we’re reminded that whoever we choose for government, Christians have a greater loyalty, to the one ruler who truly is worth our devotion and service.

But I worry about the increasingly tribal nature of our society. New technologies and social media have helped this along I think. And prejudices get formed and reinforced by a sense that we have to stay loyal to our own tribe. We no longer relate to our actual geographic neighbours, just to the tribe to which we’ve decided we belong.

Or so some of the commentators tell us. And while I don’t think they’re completely right, or I hope not anyway, neither are they completely wrong. That’s why our political parties are all over the social media, using Facebook, Twitter and of course emails to an ever greater extent. I had three emails yesterday just from one particular party, including one purporting to come directly from its leader, despite never having been a party member or supporter. As a floating voter, I do try to listen even to those I don’t naturally agree with; but people with a strong tribal loyalty will often want to shut out and stop their ears to opposing ideas or troublesome facts that might challenge where they stand. And social media makes it easier to do that, I think.

Having said that, tribalism itself is nothing new. People have always belonged to tribes. Back in my school days, we were all either Mods or Rockers, and the really keen ones tried to customise their school uniforms accordingly. And tribalism was one of the forces at work two thousand years ago in the events leading up to today’s Gospel reading. Members of the religious elite had manufactured charges against Jesus, and stirred up the crowd, because they saw Jesus as a threat to the security of the realm. Meanwhile, the Roman governor and his forces were happy enough to facilitate this man’s death, if it would keep things quiet.

“The King of the Jews” read the sign above the head of Jesus. He didn’t look much like a king though; in fact, weak, helpless and broken, he was the antithesis of a king. He hung there as the victim of the prejudices and fears shaped by the religious, cultural and political tribes to which those who crucified him subscribed.

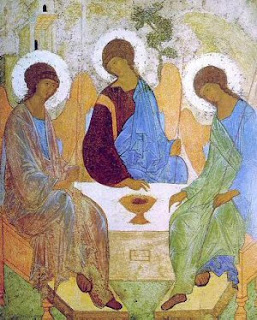

But as he hung there, there were two other men hanging with him. on three crosses. One of the men challenged Jesus. “Save yourself and us” he cried, but you get the feeling he didn’t believe for a moment that Jesus could actually do it. This man is obviously not a real Messiah. He’s weak, he’s broken, he’s humiliated. He’s going nowhere.

I feel a bit sorry for that criminal. He taunted Jesus, and couldn’t believe in him, but he was in agony, he was dying. And maybe in all this pain he was also incredibly angry with Jesus for having done nothing to stop the dreadful thing that was happening. If he could stop it, why didn’t he? It’s the other criminal who surprises me. In this most dire situation he still saw the truth of Jesus, the innocence of Jesus. He recognised the goodness of Jesus even as his own world imploded in pain and fear.

It took a criminal, justly facing the punishment his crimes deserved, to see that the most powerful person on that dark hill was the one everyone else thought of as the weakest. And that, as others would come to understand later, what looked like a cross was in fact a royal throne, and what looked like a death was in fact the defeat of death. To him, Jesus replied, “Today you’ll be with me in Paradise”.

Who would look for a king at a place of execution? Or for that matter in a manger in a cow shed? This king defies our natural expectations of kingship. Kings should never be vulnerable, or at the mercy of others. But his way is not the way of the world. A conference I was at some years ago in Brazil had as its motto “Um outre mundo es possivel” (A different world is possible). Christ the King Sunday reminds us that this King, the King who forgives and heals, who loves, who dies even for those who have mocked and denied and abandoned him, this King seeks to lead us to that different world.

I don’t expect this world any time soon to leave behind its tribal insecurities and feuds. And I doubt those who promise that after this election everything will be sunny and wonderful again, once he or she gets the keys to Number Ten. But I do hope we make some progress towards recognition, penitence and healing. We may be tribal, but our shared humanity is worth much more than our tribal fears. And no tribe has all the truth. So let’s not indulge in mockery, prejudice or fear. Let’s continue to stand for goodness and justice and truth. And let’s pray with that criminal at Calvary, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom”.